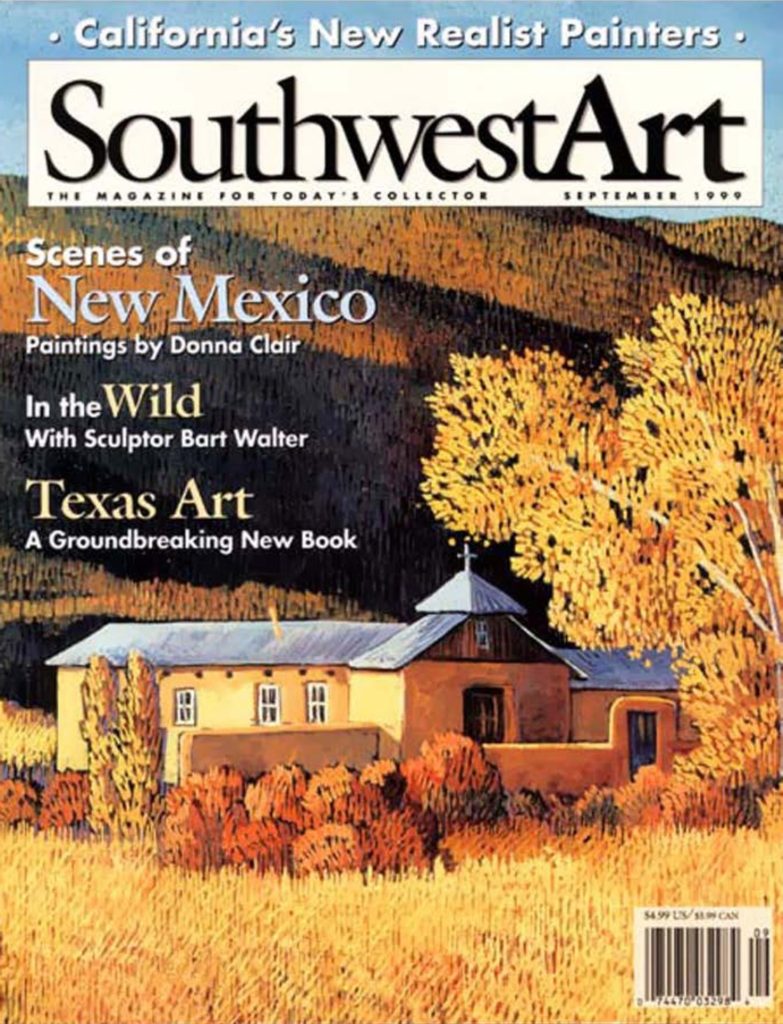

Donna Clair - A Sense of Place

Painter Donna Clair has found peace and passion in Taos

by Gussie Fauntleroy

One of Donna Clair’s all-time favorite books is Querencia by New Mexico writer Stephen Bodio. The title is an old Spanish word that refers to a deep and sometimes unexplainable magnetism that draws you to a place and holds you there. It’s a profound love of place, the feeling that the heart has found its true home.

The word also describes Clair’s feelings about the places she has lived in northern New Mexico during the past 32 years: Santa Fe, Taos, and the high mountain village of Truchas. And that strong sense of connection with the land—with the villages, the old adobe houses and churches—comes through clearly in her art. Yet, Clair admits, it was a number of years before she felt such satisfaction.

When Clair first moved to Santa Fe from Chicago in 1967, she was trailing a misconception, thinking she needed to look like an artist to be one. At the same time, circumstances were forcing her to produce an extraordinary number of paintings each year; such prolific habit transformed her into a skilled artist—not just a person who dresses like one.

Clair arrived in Santa Fe as a single mother of a 2-year-old son and 6-month-old twin daughters. She took a full-time job as a legal secretary, but to support her family she also taught painting workshops and sold her art. She painted every night after work until 2 or 3 a.m., often falling asleep in her painting clothes, then waking, changing to work clothes, and going to her job.

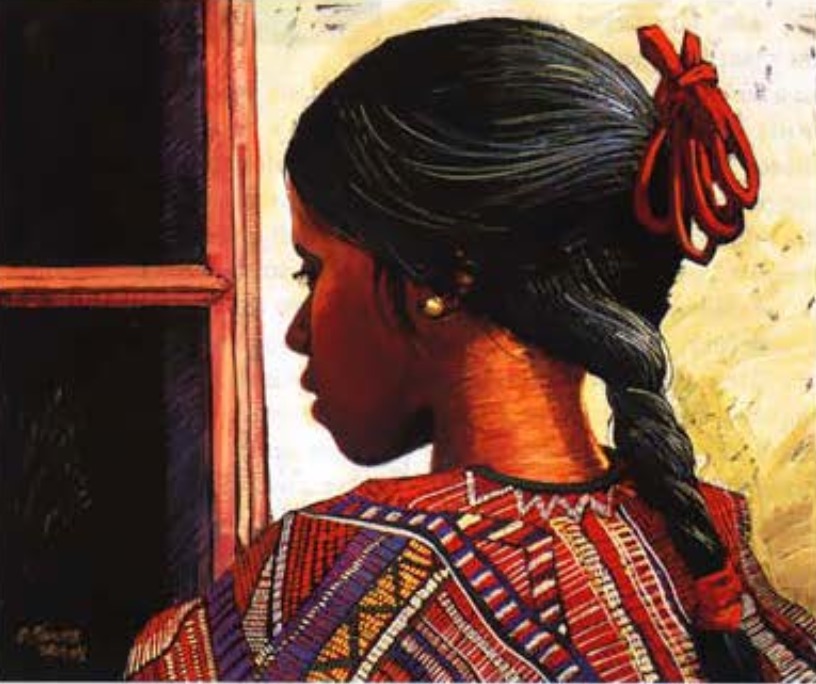

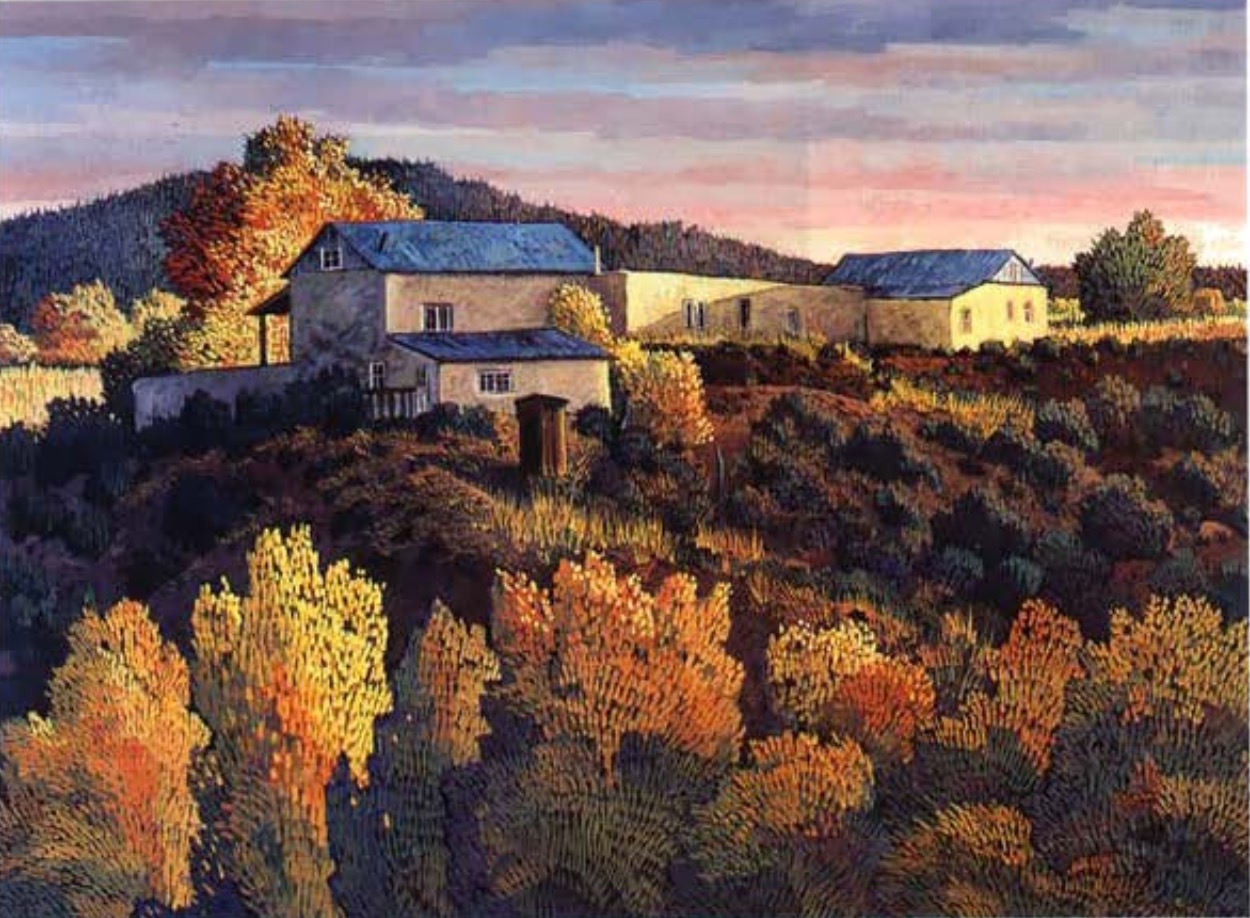

Red Ribbons [1996], oil, 16 x 20 inches

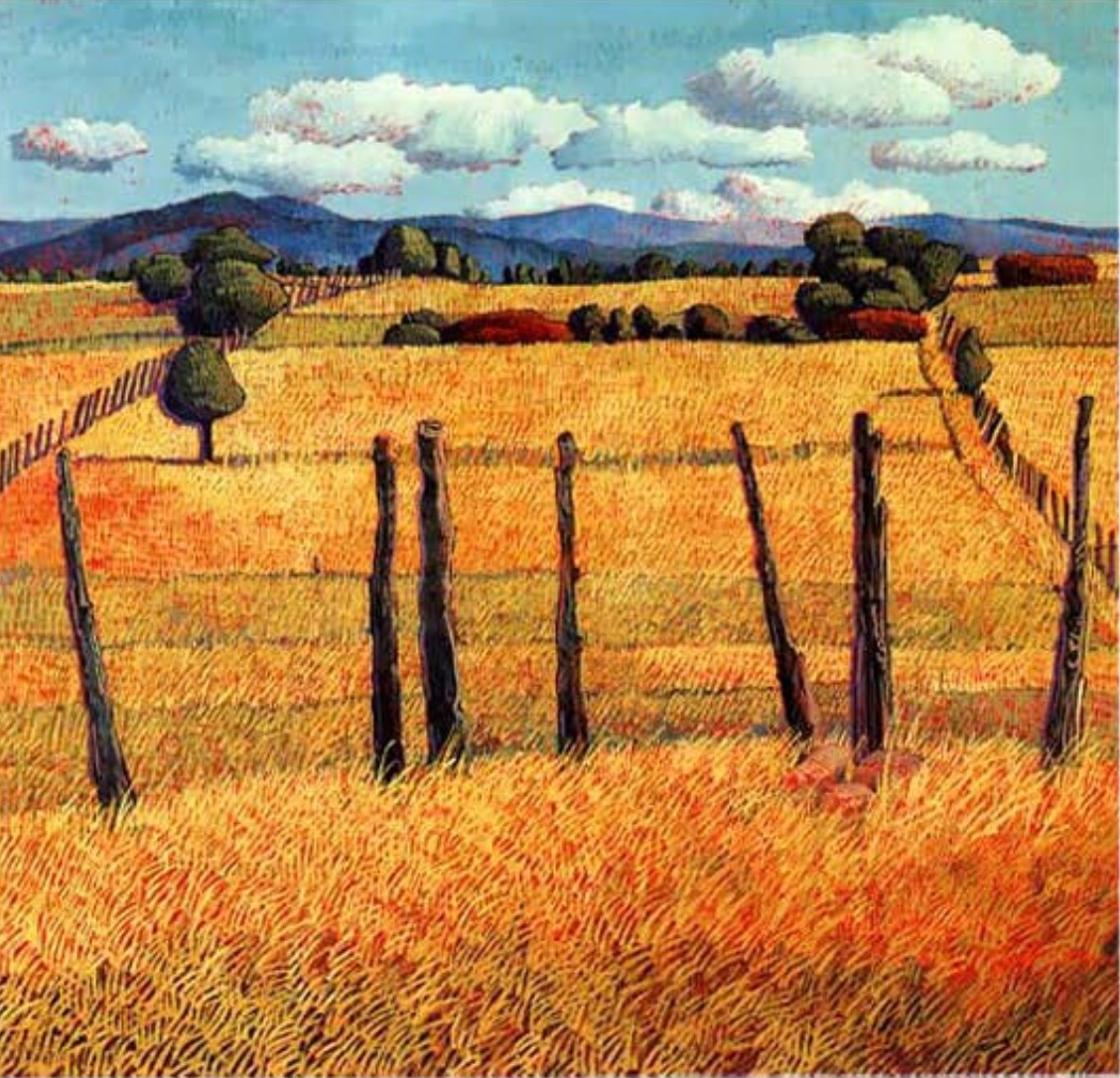

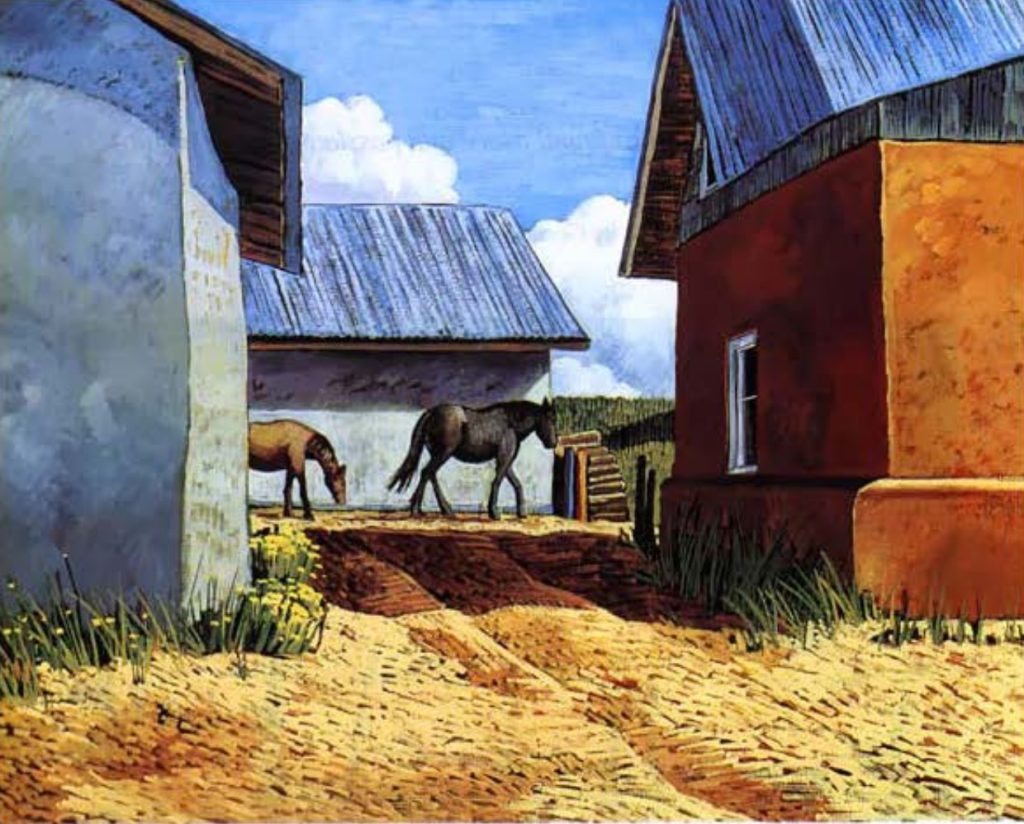

Then in 1982 Clair made a major change, moving to a horse ranch in secluded Truchas. She spent much of her time alone, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains looming nearby, a quiet sense of place starting to settle in around her. Through her art, Clair began to express her love for the land and architecture around her. Her painting changed profoundly as her technique underwent a gradual but radical transition. In earlier work Clair had used broad, smooth strokes, reflecting an interest in the Italian and French Renaissance painters. As a girl, as soon as she’d been able to ride city buses alone, she’d spent day after day in front of her favorite paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago.

When she’d been in Santa Fe for a few years, Clair bought a box of pastels and taught herself to use them. Because pastels don’t blend like paints but remain discrete colors that blend more in the mind’s eye, using them brought up two important associations for the artist: embroidery and Georges Seurat.

The daughter of Polish/German parents, Clair spent endless childhood hours doing embroidery, an essential art for women in Old World cultures. In embroidery, the colors sit side by side. In the pointillist style of French painter Seurat, they do so as well; and when Clair began using pastels, she remembered being fascinated with Seurat’s work. She would stand up close to one of his paintings and study the separate dots of color, then back away and see how the colors blended in her eye.

Strokes of color in pastel had the same effect, and eventually Clair shifted her oil-painting style to incorporate what she learned with pastels. Her paintings are created using separate strokes of pure, rich color, masterfully applied to obtain a sense of beautifully blended tones. The style also gives the work a sense of movement that complements the balance and solidity in the imagery.

“It all ties together,” Clair says, reflecting on how the various paths she’s chosen have brought her to where she is today. She sits in her kitchen in Taos, a cup of coffee in her hand, a warm smile on her face. Around her are colorful pots of flowers and green plants, Guatemalan weavings on the wall, her beloved three-legged cat lapping water from a bowl.

For Clair, there were bumps in the road early on. As soon as she showed a serious interest in art, her father strongly discouraged her, believing art to be an inappropriate career for a woman. Later, in New Mexico, she moved often while searching for a place that felt like home, living twice in Santa Fe, twice in Truchas, and twice in Taos. She painted incessantly. Whenever she felt disheartened one phrase would return to her mind: “Focus on that which abides.” And that which continued to abide was her art. “I had a lot to overcome,” she says. “What changed was me, and then the painting changed. I don’t know how I would have survived without my artwork.”

There also was and still is the abiding and supportive presence of what Clair calls her “old artist angel.” She met him only once, when she was 8. She was sitting on her grandmother’s front porch in Chicago, drawing a picture of the Blessed Virgin for her grandmother. An elderly man stopped and asked what she was drawing. When she showed him the picture he said, “That’s very good. You’re very talented. Wait here; I have something for you.”

Clair asked her father if it was all right to accept a gift from the old man. Her father, who knew the man, explained that he used to be a famous artist but was an alcoholic and now painted lamp shades at a factory. It was OK to accept his gift, her father said. The man returned and handed Clair a wooden box, which contained all his oil paints and brushes. He died a week later.

“He’s always been with me,” she says. “We all have these presences in our life he was just a manifestation of what was already there.”

Clair, who has illustrated a children’s book about Christmas in New Mexico, is planning someday to write and illustrate a story called My Old Artist. It’s one of several stories she has in mind to turn into children’s books, and it may be one of the things she’ll make time to do this fall and winter. Another will be to work in pastels again. And of course, she’ll drive around the back roads of northern New Mexico, absorbing the landscapes and village scenes she loves, sketching and taking photos. “This winter is mine,” she says. “I’m going to explore some new things, do some large paintings that I love to do.”

Throughout her life, each place Clair has lived and each set of circumstances have contributed to the way her life has unfolded. Years of prolific painting have allowed her to reach the point where technique is subsumed by a feeling of grace, as though she is simply a tool through which her paintings are expressed.

“I think in the beginning I was making paintings; now I’m allowing paintings. I just sit there and hold the brush,” she says. “I’m in a real sweet place with my life and my work.”

In the same way, being in Taos again has brought its own rewards. Clair speaks of Santa Fe, Truchas, and Taos as the “magic circle,” a round she has travelled more than once. Like three children, each place is different but none is cherished more than the others.

“Santa Fe grounded me in what it meant to live in the West,” she says. “Truchas stripped me clean; and somehow in Taos, I get to be real. I finally have an idea of who I am, and I get to do what I love to do.”

When Clair reflects on the peace she’s found, a passage from W. Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence comes to mind: “Sometimes a man hits upon a place to which he mysteriously feels that he belongs. Here is the home he sought, and he will settle among scenes that he has never seen before, among men he has never known, as though they were familiar to him from his birth. Here at last he finds rest.”

Here in Taos, at last, Clair finds rest. “Somehow in this place, life makes sense. I don’t ask why.”

Featured in September 1999 Southwest Art magazine